You’ve probably heard a lot of conflicting advice about picking good related texts for HSC English.

“Don’t pick something popular”, “Don’t pick song lyrics or Disney movies”, “You don’t really need to read your related texts…”

It can become pretty confusing after a while.

So how do you choose a kickass related text for HSC English?

In this video, we’ll walk you through step-by-step how to find a Band 6 worthy HSC English related text!

If you need some help analysing your HSC related text, make sure you check out our guide! Did you know our English tutoring Castle Hill team are experienced in supporting thousands of students successfully navigate the HSC English syllabus? Reach out today!

Let’s jump in!

What is a Related Text?

Step 1: Find the Topic Themes

Step 2: Choose a Text Type for Your Related Texts

Step 3: Understand Literary Merit of Related Texts

The Formula in Reverse

What is a Related Text?

Before we get started with actually choosing our related texts for HSC English, we need a little bit of background information on just what a related text should be. An easy way to think of this is actually in the word related.

If someone is related to you, they probably share a few of your features – maybe your uncle has the same nose, or your cousin’s gap-toothed grin matches yours. But even though there are some similarities, they’re your relative, not your twin, so there are going to be some major differences too.

That means that a related text should essentially be like a relative of your prescribed text – similar in some ways, but not exactly the same.

With that in mind, let’s get started on our 3 Step Guide to find you some awesome related texts!

Step 1: Find the Topic Themes

The first thing you need to consider when choosing a related text for HSC English is how it suits the topic! As mentioned above, you want to look for some similarities to the prescribed text – those are going to be in the themes.

A theme is defined as:

“An idea that recurs in or pervades a piece of art or literature.”

So basically it’s a key idea in a text. There’s usually a whole bunch of themes in any given text, with some being more important (major themes) and others being less so (minor themes). These themes are what you’re going to end up analysing when you write your essays!

The best place to find the themes for any topic of study is actually in the prescribed texts. Some can be obvious, for example a romance novel will have relationships as one of its key themes. It’s not always that easy though, so let’s look at just how to identify themes in prescribed texts.

Speaking of prescribed texts, if you’re studying Kenneth Slessor’s poetry for the Common Module, we’ve got you covered! Check out our analysis of his poem ‘Wild Grapes’.

Over time I’ve found 2 methods that work really well to identify a text’s themes: Moral of the Story and One Word Descriptions

The first method is really good at identifying any text’s major themes, while the second can more easily pick up on both major and minor ideas! Let’s check them out.

Method 1: Moral of the Story

What it does: gives you one or two themes that are really strong and central to the text.

Because themes are like underlying messages in texts, it’s easy to think of them as being the morals of a story. This means that they’re the important value the text is trying to teach us.

By identifying the moral(s) of a text, we are essentially identifying the key themes as well, making it really easy to figure out what a topic’s major themes are.

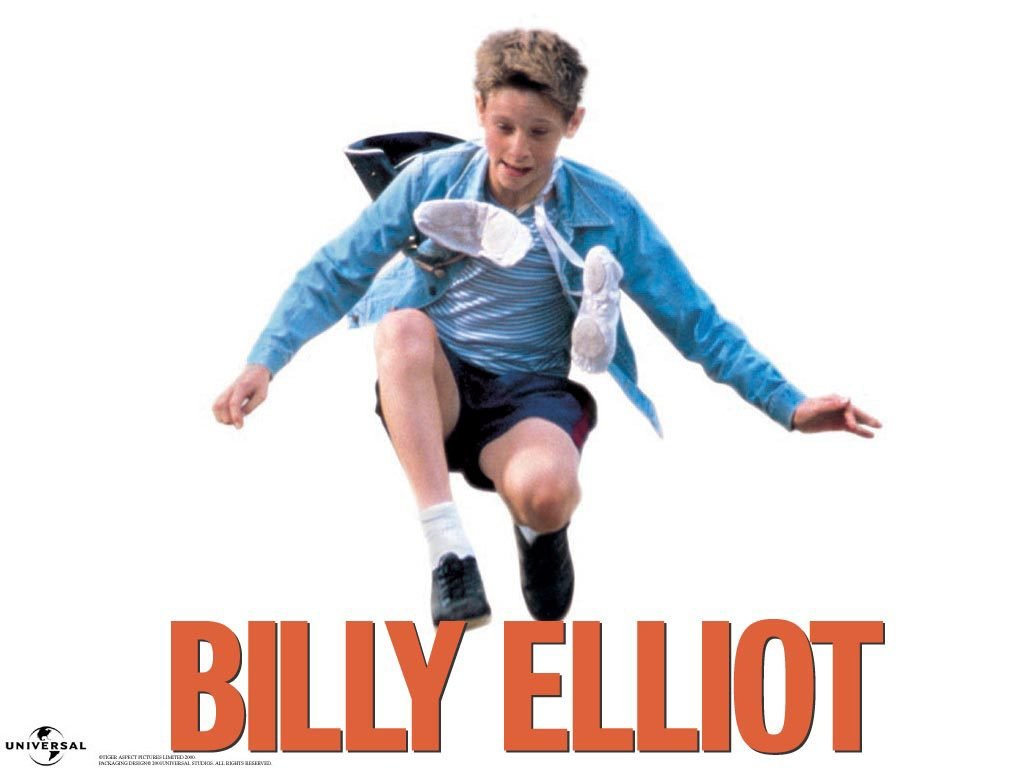

Let’s take a look at an example – we’ll use the prescribed text Billy Elliot from the Common Module: Texts and Human Experiences.

The film follows the story of 11 year old Billy, an aspiring ballet dancer who deals with the negative stereotype of the male dancer in 1980s England during the miner’s strike. Billy must learn to navigate his father and brother’s initial disapproval, societal expectations and prejudices of his small mining town whilst pursuing his passion. He is encouraged by his ballet teacher and gay best friend to follow his dream of being a ballet dancer, ultimately auditioning successfully for the Royal Ballet School and becoming a professional ballet dancer.

Even from this brief synopsis we can pull out two big morals of the story;

1. Prejudice can be overcome; and

2. Family relationships are difficult to navigate.

Those are extended themes that have been made to suit the topic (see how both relate back to the idea of human experiences) but in simple terms they could be considered themes of prejudice and relationships.

You’re best off applying this method to several different prescribed texts, otherwise you simply won’t have enough themes to use later on.

Action Point:

Think about the last prescribed text you studied – what were the 2 biggest morals in the story?

Identify them and turn them into an extended theme like the ones above for the topic that your prescribed text was for!

Method 2: One Word Descriptions

What it does: gives you a whole lot of themes to work with, though not all of them are central to the text.

This method isn’t as precise as the first, but it is very good at helping you identify a whole range of themes quickly! This gives you lots of idea to work with, which in turn often leads to finding interesting or uncommon themes to explore.

The easiest way to come up with themes using this method is to ask yourself questions about the text and answer with one or two words.

We’ll use Billy Elliot as an example again.

Q: What is Billy Elliot about?

A: Breaking tradition.

Q: What difficulties does Billy face?

A: Gender stereotypes, prejudice, family relationships.

Q: How does Billy keep going in the hardest times?

A: Taking risks, determination, courage.

Even from these three questions we have plenty of different ideas we can work with;

Breaking tradition

Gender stereotypes

Family relationships

Determination

They’re pretty basic at the moment, so we have to expand them to suit the topic properly. They could become:

- Breaking tradition and gender stereotypes are a necessary part of the human experience

- Maintaining family relationships is a universal conflict in human experience

- Determination can lead to growth in one’s human experience

With this method you’ve essentially given yourself a bunch of ideas to work with and get to choose which ones you like best later on. Plus, if you find you need more themes it’s only a matter of asking more questions!

Action Point:

Like last time, think of a prescribed text you recently studied – now ask yourself these 3 questions and give single word answers;

- What is it about?

- What is most important to the main character?

- What motivates the main character?

Expand your single words into themes to suit the topic and there you have it!

Which is better?

To be honest, using both methods together is the best way to go.

Even though it may seem like a little more work, using them both allows you to identify the most major and minor themes possible, which is going to be really important in the long run.

Plus, it means you’ll know exactly which themes are central to the story (those from method 1), so you can focus more on those.

So now that we know our key themes for the topic, what do we do next?

Create a List of Your Themes

From the themes we gathered using the methods above, create a list of all the themes related to the topic you’re studying.

Keep this on hand for the rest of the process, as you’ll continue to refer back to it to make sure that the texts you’re looking at suit the Common Module.

If you look at your list and already know a few texts that feature similar themes, that’s great! It means you’ll use the next two steps of the method in different ways – we’ll cover that when we get to it.

Action Point:

Using the themes you gathered yourself jot down a quick list of themes and any others that come to mind!

You can use this later, both for this article and your own study.

Step 2: Choose a Text Type for Your Related Texts

One of the biggest places students let themselves down when it comes to choosing a related text for HSC English is when they don’t consider text types. It may seem unimportant, but making sure that you consider the type of text you choose just as much as you consider it’s context is key to selecting a great related text.

What texts types are there to choose from?

- Film

- Novel

- Short story

- Poem

- Play

- Song (only if you have a musical background)

- Speech

This list is ordered by popularity, but that doesn’t mean you should avoid the top few types just because they’re common.

Novels, films, short stories and poems can all be analysed incredibly well so long as they’re given the right consideration. Plays are usually a little trickier to analyse because of their format (and people don’t like reading them), as are speeches, and songs should only be used if you have a musical background (more on this later).

A first piece of advice: don’t choose a movie just because it’s ‘easy’!

That’s not to say don’t use films at all! I actually used films for most of my related texts in Year 11 and 12 English and went really well – but only because I considered the text type first. But what exactly does that mean?

There are two questions to ask yourself when choosing a text type:

- Is it the same text type as the prescribed text?

- Can you write about the text type?

To understand why these questions are important let’s take a closer look at them.

Question 1: Is it the same as the prescribed text?

This one is pretty simple – whatever text type your prescribed text is, don’t choose a related text of the same type.

So if your prescribed text is a novel choose a film, poem, or something else instead. Likewise, if you’re studying a play in class don’t choose another play for your prescribed text.

It may seem obvious now but a lot of students forget to take this into consideration when choosing their related texts and end up with two of the same type.

Though this isn’t necessarily the end of the world, it’s much better to vary it because it shows markers that you can analyse different text types. Plus it means you get to look at different type-specific techniques and how they’re used to show the same themes.

Also try to mix up related text types between topics/modules. If you’re using a film for Module A, go for a poem in Module B. It’ll help improve the range of types you’re comfortable writing about!

Action Point:

Think about the last three prescribed texts you studied in class – what text types were they?

Write the types down on a piece of paper for later

Question 2: Can you write about the text type?

Now I know what you’re thinking – “What do you mean can I write about it? I’m in my final years of high school, obviously I can!” – but hear me out.

Writing about a text type isn’t as simple as mentioning that your related text is a poem in your introduction. What it’s actually about is recognising and analysing the type-specific techniques within the text.

What’s a type-specific technique?

These are the techniques that you can only find in certain text types or are used in very specific ways for certain types.

For example camera angles, wide shots, costuming and lighting are techniques you’ll only find in film, whereas soliloquies, stage directions and asides are typically specific to plays.

Basically type-specific techniques are what one text type has that none of the others do – it’s what makes it the type that it is.

A Warning on Using Songs:

You have to take special note when it comes to choosing songs, as a lot of students do this and end up getting poor marks. If you choose a song for your related text, you have to have a musical background. This is purely because the text includes music and therefore you have to analyse the music in order to do well. Too many students only analyse the lyrics and end up being disappointed in their marks, so unless you’re a music whiz as well, avoid using songs!

So why is all this important?

Because for whatever text type you choose you’ll have to make sure to focus on the type-specific techniques, so choose on that you know about. If you really enjoy writing about the different techniques in novels, go for it! If you know your analysis skills are stronger in the film department try that instead. Play to your strengths where you can and you’ll have a better essay in the end.

Action Point:

Copy down the list of text types from before and rank them from 1 to 7, with 1 being the type you’re most comfortable writing, 7 the one you don’t want to touch with a six foot stick.

You’ll need this in a minute so do it now!

Making the Choice

Now that you’ve asked yourself what type your prescribed text is and whether you can write about the type you have in mind, it’s time to pin down a text type.

You probably already know what you want to use just from thinking about it, but if not the easiest way to do it is by knowing your options.

Follow these steps to pick your text type:

- List all the text types

- Immediately cross off whatever type your prescribed text is

- You can also cross off the ‘Song’ category if you don’t have a musical background

- Then number your top 3 of text types you’d like to write about – you can use your numbered list of text types from earlier to figure this out.

- From there, choose one of your top three and you’re ready to go!

The reason you don’t always necessarily want to go with your number 1 text type is purely because otherwise you’ll probably end up using the same type every time. Remember to mix it up a little!

Action Point:

Using your list of past prescribed texts and your text type preferences, create a list like the one above for each of the prescribed texts you wrote down

This way you know exactly how the process works for when you need to choose a related text next time.

Step 3: Understand Literary Merit of Related Texts

The reaction I get from students when I mention literary merit is always the same; “Literary what?”. Before we get started let’s clear up just what we’re actually talking about.

Definition:

Literary merit is the quality shared by all works of fiction that are considered to have aesthetic value.

The concept of “literary merit” has been criticised as being necessarily subjective, since personal taste determines aesthetic value, and has been derided as a “relic of a scholarly elite”.

What that means:

Literary merit is a quality that is found in texts that are seen as being of ‘proper’ and meaningful value.

Many people think this is baloney, because whoever decides what does or doesn’t have literary merit is obviously going to be biased in some ways.

It’s a little tricky to understand, but I used to think about literary merit as being the kind of thing Jane Austen novels and Alfred Hitchcock films have.

Usually texts that have literary merit are older and have stood the test of time.

You know how your teachers sometimes get a far-off look in their eyes and talk about ‘The Classics’? Those have literary merit.

You’re probably wondering why this matters, and I’ll be honest with you – only because the markers think it does.

The point is that a lot of the people who are going to be marking your essays think that literary merit is the bees knees, so you’re going to want to choose a text that does have literary merit.

“But wait,” I hear you say, “Does that mean I have to choose some boring old people book?”

Not at all! Choosing a text with literary merit is actually pretty easy if you know where to look, and fortunately for you I have a cheat sheet!

Literary Merit Cheats

The thing you need to know about literary merit is that it’s what a lot for critics use to judge plays, poems, short stories, films and novels.

That means that the texts that the critics think are amazing are probably going to be the kind that your markers think are awesome too.

Obviously, this means the best place to find possible related texts is by looking at what has won the big awards!

Films

List of all the films that have won the Oscar for Best Picture

List of all the films that have won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay

The Time Magazine list of All Time Top 100 Films

If you’re more into independent and foreign film you can also try the Grand Prize winners of the Cannes Film Festival.

Novels

You can usually cheat with this and just google ‘best novels’ or ‘top 100 fiction books’

It’s also a good idea to check out Time Magazine’s list of All Time Top 100 Novels

The past recipients of the Man Booker Prize if you’re feeling brave

Short Stories

It can be harder to figure out which of these have literary merit, but checking out the winners of the Frank Conner International Short Story Award or any other similar awards

If in doubt, Tim Winton’s The Turning is a great collection of short stories many English teachers love to see as related texts.

Poems

These are a little trickier too but you can try this list of Griffin Poetry Prize winners

You can also Google something like ‘best poets of all time’ and cheat a little.

If it’s written by T.S. Eliot, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Emily Dickinson, Lord Byron, William Blake, William Wordsworth, Maya Angelou, Sylvia Plath, John Milton, Rudyard Kipling, Emily Browning or Alfred Tennyson, you can’t go wrong — except for the fact that some of them are being studied in Extension 1 English (make sure to check!).

Plays

Shakespeare. If you really, really, really don’t want to do Shakespeare you can try something like this list of the best plays in the last 100 years, but I mean… Shakespeare is right there

Markers are also super impressed with Australian playwrights – Louis Nowra, Patrick White (one of Elizabeth’s favourite!), Joanna Murray-Smith, Nick Enright, Dorothy Hewett and Ray Sewell are all Australian literary monoliths!

Or you could cheat and refer to this list of the Best Australian Playwrights.

It’s now simply a case of going through these lists and seeing if you can pick out any texts that you like!

Use the text type you chose in Step 2 to figure out what kind of text you’re looking for and your list of themes from Step 1 to figure out which of the texts you find will actually work.

Of course, you may not find exactly the text you want in these lists, but that’s okay! They’re really meant to give you an idea of what literary merit looks like, so if you pick up your copy of Die Hard you can immediately say to yourself “That probably wouldn’t show up on one of those lists. Maybe I need to choose a different related text.”

Action Point:

From the text types you chose in step 2 and the themes you jotted down in step one choose a list and look through it to find a related text for ONE of the three past prescribed texts you’ve been working with.

The Formula in Reverse

While the formula as a straightforward process is awesome and can help you discover some amazing related texts for HSC English, it’s not for everyone.

So, for those of you who prefer to work with what they know or who already have a text in mind, simply use the formula in reverse!

Step 1: Themes

Do the themes of your related match your prescribed text? Do Step 1 as usual, then use the same methods on your potential related text to find its themes. Are they similar?

If they are keep moving forward, if not maybe try finding a text better suited to the topic’s themes.

Step 2: Text Type

This one is easy. Ask yourself these two questions very similar to the ones in the regular steps, just do it with your potential related text in mind.

Is your prescribed text the same type as your related text?

Are you comfortable writing about this related text’s type?

If you answered yes to both of them you’re good to go! If not re-evaluate your text type choice to try to find a better one.

Answer any questions you get in your exam properly by understanding the key HSC English verbs!

Step 3: Literary Merit

This step is up to you really. First check to see if your chosen text has won any prizes (hopefully not any Golden Raspberry Awards though) and if it has roll with it.

If not take a look at the lists of text with literary merit in step three and ask yourself “Could my related text be on this list? Is it like these texts?” If the answer is yes you’re fine, if not you may want to choose a new one.

Action Point:

Have a bit of fun this time! Grab your favourite book or movie and see how awesome or lame it would be as a related text for the topic you’re currently studying in English.

So there you have it – the formula to choosing a great related text!

Obviously results are going to vary based on your personal preferences, the texts you may or may not already have in mind, what topics you’re studying and the like.

The point is really to give you a framework that will help you at least narrow it down and give you some criteria to make finding a strong related text a little easier.

The main things to remember are themes, type and literary merit. If you can get these down pat and always take them into consideration when choosing your related texts, you’ll have an awesome outcome every time.

Looking for related texts for the HSC English Common Module? Check out our complete list here! Need some help with analysing visual texts? Check out our 3 step guide here!

Looking for some extra help with your HSC English related text?

We have an incredible team of HSC English tutors and mentors who are new HSC syllabus experts!

We can help you master your HSC English related text and ace your upcoming HSC English assessments with personalised lessons conducted one-on-one in your home or at one of our state of the art campuses in Hornsby or the Hills! Get support from our wonderful tutors in Bella Vista if you’re based in the Hills.

Check out our Hurstville HSC English tutoring options to ace your HSC English assessments!

We’ve supported over 8,000 students over the last 10 years, and on average our students score mark improvements of over 20%!

Nail your related-text analysis with personalised Mosman tutoring! Closer to Western Sydney for tutoring? We provide K-12 English support in Parramatta too!

To find out more and get started with an inspirational HSC English tutor and mentor, get in touch today or give us a ring on 1300 267 888!

Maddison Leach completed her HSC in 2014, achieving an ATAR of 98.00 and Band 6 in all her subjects. Having tutored privately for two years before joining Art of Smart, she enjoys helping students through the academic and other aspects of school life, even though it sometimes makes her feel old. Maddison has had a passion for writing since her early teens, having had several short stories published before joining the world of blogging. She’s currently studying a Bachelor of Design at the University of Technology Sydney and spends most of her time trying not to get caught sketching people on trains.